“You can’t stick to something you like”: an interview with Frédéric Tiffet

In this exchange, Frédéric Tiffet talks about the nuts-and-bolts aspects of his practice, the dream he had at 20 that set his life’s course, and the richness that comes from slowness, patience and the willingness to lose a painting in the course of following a blind path.

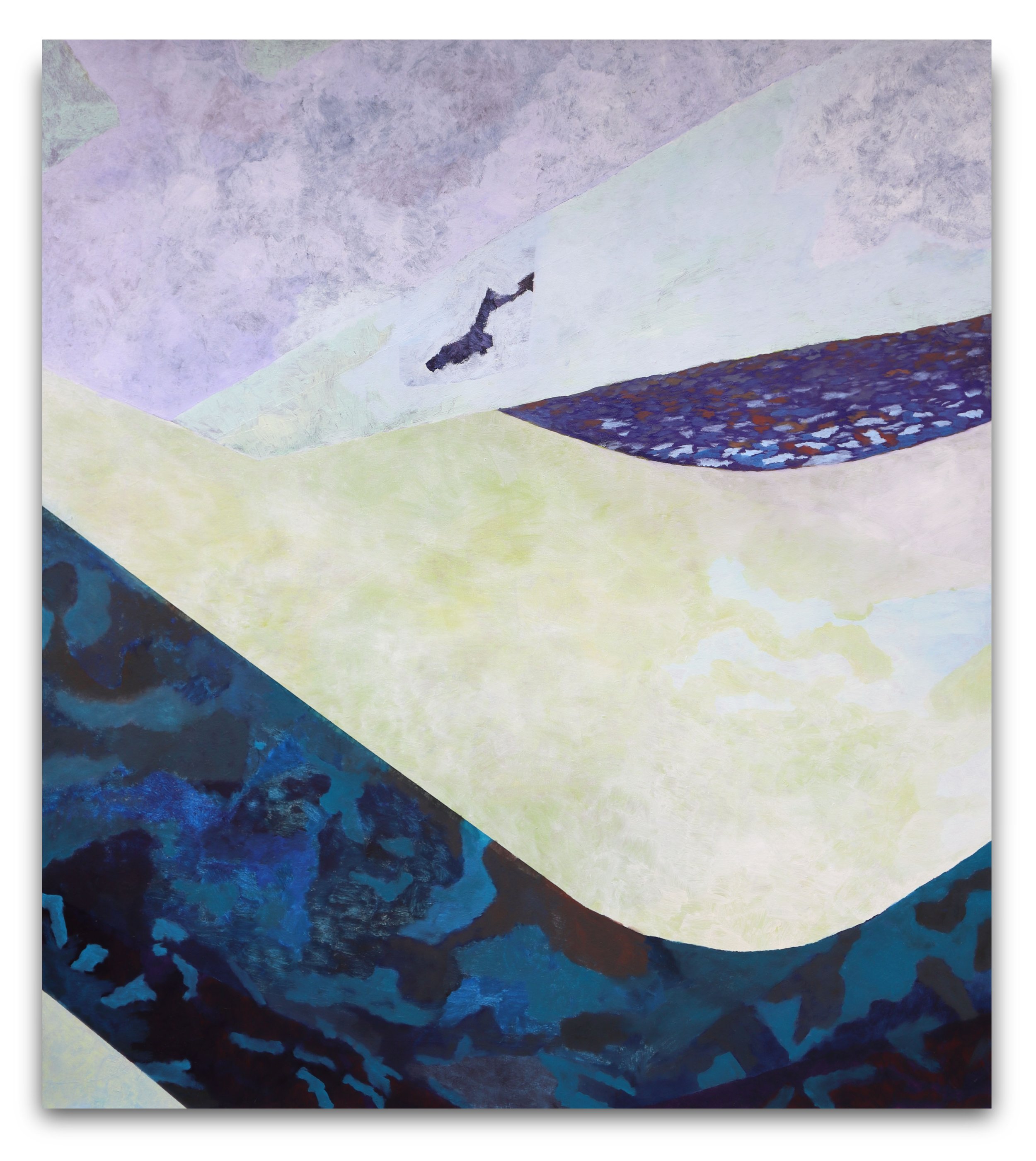

no floor, 2023. Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches.

(Natalie) Can you talk a bit about how your paintings begin?

(Frédéric) When I start a new painting, I don’t really care about what is going to happen in the first stage, because I know it will only become a ruin, erased by the proceeding stages. It’s like a free-zone where I can work everywhere on the canvas at the same time and let the structure and composition be considered later. It’s such a long process for me to find the image, to find the diagram, that I can’t stop at each stage to structure it. It’s like the further along I am in the painting, the more my head will be required, and the biggest decision won’t happen until the very end.

For me a sign of a successful painting is that I’m already getting ideas for the next one. You have mentioned that the paintings in your studio, at various degrees of completion, can influence each other. Do they spur the beginning of new ones as well?

I would say that sometimes, yes, they will spur the beginning of new ones. Since new techniques and new spaces have been learned in the process of finishing a painting, I will know from one painting to another what kind of structure I’m looking to, and in doing so I will be less and less blocked between phases because I will be more conscious about the different reactions of the matter. I will know more that if I’m putting this color beneath a specific glaze, I will get a particular tone. So as an alchemical process, yes, I’m gaining more and more knowledge from one painting to another.

But at the same time, after years of painting I find that each image actually develops its own ideas, its own spaces. And even if my technique is growing in parallel with my practice, I tend to follow specific steps, at each moment; and this brings me, most of the time, to being free to react, with my hand, step by step, along an unknown path that I won’t know the end of until I reach it.

Installation view: “everything is never finished” Paintings by Frédéric Tiffet at KIPNZ (2023)

(left) one’s own glyph, 2023. Oil on canvas, 40 x 32 inches; (right) suspension, 2023. Oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches.

Related to this question - and related to the title of the show, “everything is never finished” - what is your attitude towards the decision (or not) that a painting is finished? Are you going to paint over any paintings that come back to you?

Yes, in some cases I will. Because even if each painting works on its own, every painting that I made in the past and the one that I’m making in the present are slowly defining, deciphering, a whole world. The task is to get, as I’m getting more and more experience in reading the world that I’m making, to the most precise definition of this or that world. It is really ambiguous for me, enigmatic, to define what I’m doing, and I like it that way, thinking that maybe in the last painting that I’ll make in my life, at 90 years old if I manage to get there, I would be at the most precise point of a painting. I dreamed a couple of times of a whole room, it looked like a cavern of some sort, where I saw all those paintings. And they were very good, but I’m not actually near that. The first time I dreamed of this room, I was 20 years old. When I woke up I knew that I would paint all my life in order to make those paintings I saw in this dream.

Thinking this way helps me anticipate the long process of making oil paintings, and helps me to free myself from the fear of losing a painting, and accepting failure.

So in this way every painting that remains in the studio will be contaminated by the new ones. In the first decade of my painting life, I might have painted 200 paintings, but they are all now hidden in 20 very thick paintings. So no images, only memory. But they come back, these memories, from time to time: when I’ll make a mark somewhere, an old apparition will pop out again, and again.

What is your palette? Do you mix from a large or small group of colors? Any new tubes you’ve bought recently that got you excited?

I normally work with just a couple of tubes. I love to mix. For me, everything is already there: using a cobalt blue, a Prussian blue, a cadmium light yellow, a cadmium red deep, and titanium white, I will get a whole spectrum of color. And as the linseed oil (where my brushes stand after use) gets dirty, this dirtiness turns to earth tones, browns and greys with these glimpses of lightness created by the new color that emerges from this whole chaos: I am actually bringing the palette down into the earth or out into the cosmos. Something is being petrified, or sublimated. So I don’t start with many colors because it’s a joy to make them appear, and I love to be surprised. There aren’t any particular tubes that get me excited, but rather some colors that come out of the mixing, like strong reds and violets. And a lot of the time I create a color that I won’t be able to use, like reds - red is the hardest color to use for me, so hard. It drags too much of the attention, it needs to be in relation to an adjacent color to calm it down a bit. Or, to be all-over in a monochrome would work too.

What do you use as a mixing surface? What kinds of brushes? What kinds of solvents do you like?

I mix my paint on old windows I find in the street, and since I work in a poorly ventilated studio, I only use walnut oil as a solvent. It’s not at all toxic - the turpentine I used to use made me dizzy, as if I was smoking weed all day. And I normally use small brushes, even working on big formats. I love to repeat the gesture as though I'm scratching stones to find gems. If I’m filling a big space in a light blue, for example, I would do it for hours, aggravating the tendonitis in my forearm. It’s something I could do in 10 minutes with a big brush like an action painter would do - but in doing it patiently, something is revealed. As the subsequent coats of paint build up, the surface looks older: the past is coming. I feel like if I’m doing it slowly I discover the image, but if I’m doing it fast I only appose. (E.g., the colours are merely placed side by side, or juxtaposed. Ed.)

Can you talk a bit about the enigmatic figures that appear in some of your paintings? Like in “hypérion,” “noli me tangere” and “rivage”, for example?

In the process of painting, figures, faces, or defined objects will frequently appear out of the chaos. And sometimes, when I find the apparition to be sound enough to exist with the rest I will define it more. But as the painting travels through each phase, it will sooner or later disappear. And the reason is purely an optical matter. I like my eye to roll around and inside out of the painting, to find labyrinths, logical problems, traps, and so on. So a figure for me will block this active contemplation, because the eye will stop at the figure and start to reach for a narrative. But in hypérion and in noli me tangere (in rivage it is obvious: it is a portrait of a ghost and it fills the entire plane) they succeed in standing in the space. I don’t know why but they manage to persist throughout the whole process, without altering the structure (of the painting).

noli me tangere, 2023. Oil on panel, 40 x 48 inches

What is your relationship with “risk”? One of the things I like about “impossible” is that the viewer feels almost present with your decision to overlay the white on that right-side two-thirds of the panel. Can you talk about that moment?

I think I started doing good paintings when I began to risk losing everything in a big move. I mean, you can’t stick to something that you like; we are not here for that. There is a whole jump, a whole and empty void that paintings demand. It screams for a move in your head, and you better go for it. In a book he wrote on Edvard Munch (So Much Longing in so Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch), Karl Ove Knausgaard talked about the time he met Anselm Kiefer. When he saw Kiefer covering a beautiful painting with liquid lead he asked him if he was scared to lose a painting. Kiefer answered that all painters are iconoclasts. Isn’t that the best answer!? We cannot be obsessed with images if we want to continue painting; we would be stymied every time. Painting forms itself out of the chaos, from the beginning to the very end, and it can go very far if we aren’t scared to lose it. I’m thinking about Gilles Deleuze talking about Bacon’s paintings in courses he gave at Université de Vincennes Saint-Denis in 1981, where he talks about chaos-catastrophe. He explained that at some point, out of this chaos of composing a structure, a catastrophe needs to happen. Guston talked about it like going into a trial, where at some point a judgment will fall and it changes everything in the life of the painting. So in impossible, this moment happened in a very obvious way, where we can see that these lines of white were the last move and covered something underneath that was completely different. But it happens all the time, and even in-between phases. I sometimes feel very much excluded from the object I’m creating. I don’t know where those big decisions come from, but if I don’t welcome them, it is there that I’ll be stopped.

impossible, 2023. Oil on panel, 48 x 72 inches

What is the last exhibition you saw that really affected you?

I would say the retrospective of Philip Guston’s work at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the summer of 2022. I had seen a couple of his paintings here and there in the past, read a lot of books on him, and studied his structure and composition carefully; but to be submerged by his paintings in big rooms, was a very introspective, moving experience. It felt like all of the paintings were one big painting, making up a lifetime. It felt like we could piece them together to complete the puzzle. And I was really affected by his dark paintings - the ones from his abstract expressionist phase of the fifties and the figurative ones in the seventies. They made me want to blacken my palette, which was at that time very pale, very snowy, like winters in Montreal.